Marine debris in the Chesapeake Bay watershed

The Chesapeake Bay watershed

The Chesapeake Bay watershed encompasses 64,000 square miles of area that drains into the Bay. 150 large rivers and streams flow into the Chesapeake Bay watershed. More than 100,000 tributaries consisting of streams, creeks and rivers, flow into the watershed. That is a lot of water! The Chesapeake Bay watershed covers parts of Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, West Virginia, New York, and the District of Columbia. In addition to the 18.2 million people that live in the watershed, may iconic species and wildlife live in the Chesapeake Bay. These include species like blue crabs, oysters, and striped bass.

Point source pollution and non-point source pollution

Pollution that enters the Chesapeake Bay comes from many sources, which are divided into two categories- point source pollution and non-point source pollution. Point source pollution is waste which can be attributed to a specific physical location. Point source pollution usually refers to nutrients discharged from wastewater treatment plants or factories. Non-point source pollution is pollution that cannot be attributed to a clearly identifiable, specific physical location. Non-point source pollution includes nutrients that run off croplands, feedlots, lawns, parking lots, streets and other land uses. It also includes nutrients that enter waterways via air pollution, groundwater or septic systems. Litter carried to the Chesapeake Bay is an example of non-point source pollution.

Types of pollution

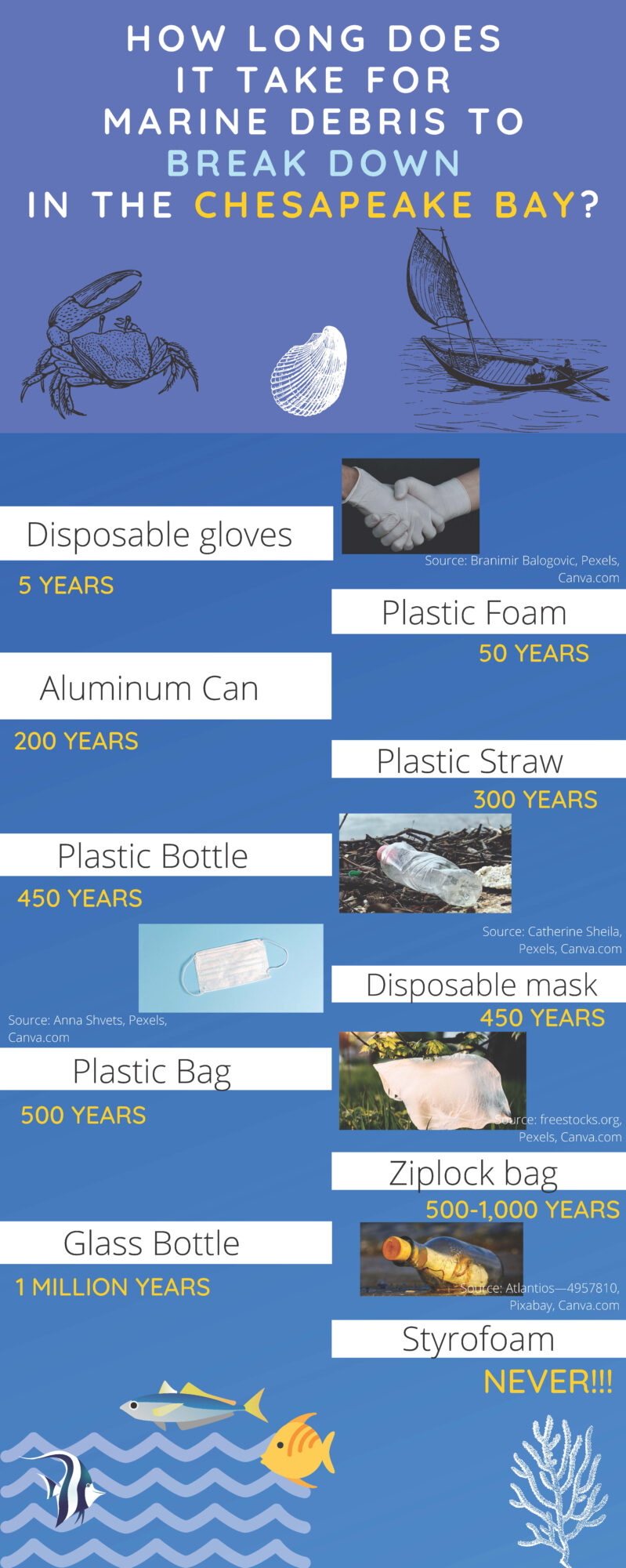

Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, the amount of single use masks and gloves has increased, presenting a new challenge for non-point pollution in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Did you know that disposable masks can take up to 450 years to decompose? Disposable masks and gloves are lightweight and easily carried by wind or runoff, eventually making their way to a body of water. These types of items are considered marine debris- a solid manufactured material deposited in a marine environment. Marine debris threatens aquatic species and could be dangerous to human health. If possible, consider using a cloth face mask. You can learn how to make one on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website. If you choose to wear a disposable mask or gloves be sure to throw them away properly instead of littering to prevent them from becoming marine debris.

Effects of marine debris

Marine debris can entangle marine species who may mistake items like plastic bags, straws, or plastic pack rings for food. Entanglement isn’t the only threat that marine debris poses to aquatic species, when larger plastic pollution breaks up into smaller pieces it’s called microplastics. Microplastics float in the water column and can be consumed by species like shrimp, fish, whales, and sea turtles. The consumption of microplastics bioaccumulates up the foodchain and may be impacting human health. When you can, limit the number of single-use plastic materials you use per day to decrease the amount of litter entering the waterways and contributing to marine debris.

Actions to take

Here are some simple, yet effective actions that you can take now!

- Go plastic free: try not using any single-use plastic items for an entire week! If you’ve been successful, try going a whole month to decrease your plastic usage and waste.

- Recycle plastic bags properly: often, plastic bags shouldn’t be disposed of in single stream recycling receptacles. Some grocery stores accept plastic bags for recycling. Check with your local recycling center to see how best to dispose of plastic bags or reuse them at home.

- Refuse: refuse to buy items or food products that are unnecessarily packaged in a way that creates an exorbitant amount of waste.

- Do not litter: if it is not possible to avoid using sing-use plastic products be sure to dispose of them properly.

- Try reusable masks: this limits the number of disposable masks being produced and entering our waterways.

Additional resources:

- A Scientific Cleanup Lesson Plan

- Marsh Munchies Game

- Action Project: Plan a Stream or River clean-up event

- Bay Backpack Blog: Why Teach about Marine Debris?

About the author: Carly Sniffen is an Interpretive Outreach Specialist for the Communications Department of the Chesapeake Conservancy.